Evolution in Human Societies: the Commitment to the Constancy of Fundamental Justice

“Impatient with the present, hostile to the past and deprived of a future, we really did then resemble those whom justice or human hatred has forced to live behind bars” (Camus 57). In his novel The Plague, Albert Camus explores how, during unprecedented times of pestilence, resulting in rapid alterations to everyday mundane activities, different people come to question the banes of their existences and justice itself when faced with what appears to be eternal suffering. Throughout the story, we are presented with the immensely disturbing aspects of a tragic (yet rather familiar) situation of how a society and its people gradually deteriorate in social, economic, and legal aspects. Progressively, everyone begins to lose intensity in their emotions, while the impending feelings of helplessness and hopelessness escalate. Justice is questioned, and judgment is ridiculed.

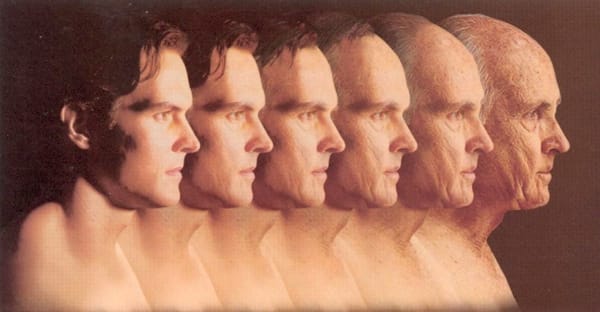

From the era of ancient Greek civilization to today's more modern, hustle-embracing societies, the core elements of justice have been carried to withstand the test of time. Yet, it comes as no particular surprise that despite the efforts to preserve such a fundamental concept, the various perceptions of how people practice and apply justice have become modified. In philosopher Ryan Holiday’s Right Thing, Right Now: Good Values, Good Character, Good Deeds, he explains how acting in a just manner is not optional. Famous historical figures and heroes alike share similar stories because of the unanimity of their commitment to being a good person. “Because that’s what justice should be—not a noun but a verb. Something we do, not something we get” (Holiday xxiii). As with most things, a change in the tide calls for an innovation in approach. Even so, recently adopted views seem to further disassociate justice from the individual. Hence, the continuous inquiry of learning to balance newer adaptation while committing to the constancy of fundamental justice becomes increasingly crucial.

Formerly, justice went beyond the idea of egalitarianism, for it was a personal quality and value set to strive for; an individualistic commitment to leading a fair and virtuous life. Outside of debates, discussions, and decision-making, people were more attached to the notion of presenting themselves as a just person. Comparable to how a medieval knight was focused on displaying a chivalrous attitude, justice was seen as a prime factor in what made a person “good.” In other words, justice was more than the concept of equality; it was a highly admirable and altruistic lifestyle to lead. Being one of the four widely recognized cardinal virtues (wisdom, courage, justice, and temperance), it provided a moral compass for the individual. A guidebook on approaching life as an ideal citizen, in the most direct sense.

More recently, however, justice tends to have a less significant emphasis on the individual. Instead, it is regularly being used merely as a term meant to portray a distant idea, primarily concerning the courtroom, not the average citizen. Some may even consider justice as having been degraded within the minds of people because it lives on as a testament provided for by a verdict, as opposed to a virtue or moral code. Intriguingly enough, that is not to say that justice has become any less discussed by the people in society. In fact, there has been a large amplification of discussions regarding justice, inevitably as a result of social media. People who previously would not engage in such debates are now able to pitch in their brief thoughts and opinions because our fast-paced technology is able to reel in wide audiences. Initially, discussions relating to justice started as a philosophical set of principles. John Stuart Mill, John Locke, and Robert Nozick expanded the connection to human rights, governance, and legal and political states. As we continue to witness the progression of these debates, it is crucial to recognize that it is part of our natural cycle of evolution, keeping us inquiring and wondering about our future.

It is nearly universally accepted that being fair is intrinsically right. The question of whether there is a fair metric for putting “fairness” on a scale is then posed. Despite that, people have an instinctual inclination to follow comfort over rightness, a state in which decisions are based on emotion or attempts to “fit in.” A sense of helpfulness is lost, and everything becomes immaterial, negligible even. We witness this in Camus’s novel, “They no longer made choices. The plague had suppressed value judgments. [...] Everything was accepted as it came” (Camus 142). Hence, to have a public interest in justice, it is important to consider a plethora of new perspectives.

Ultimately, it is not dependent on us to become either irrationally cynical or overly praising of how justice has changed over many centuries, but rather, to notice the inherent distinctions impacting our understanding of justice. Therefore, being applied to the practice of justice itself, we tend to see modern rulings often combine previous ideologies and newly founded ones to reach many intricate issues in today’s society. As a result, we should all strive to strike a fine balance between re-introducing justice to the individual as the core of morality and learning to integrate more contemporary views to flow with the current right.

References

Camus, A. (2002). The Plague (Penguin Modern Classics) (T. Judt, Ed.; R. Buss, Trans.). Penguin UK.

Holiday, R. (2024). Right Thing, Right Now: Good Values. Good Character. Good Deeds. Penguin Publishing Group.